The Cities We Need: Essential Stories of Everyday Places by Bendiner-Viani

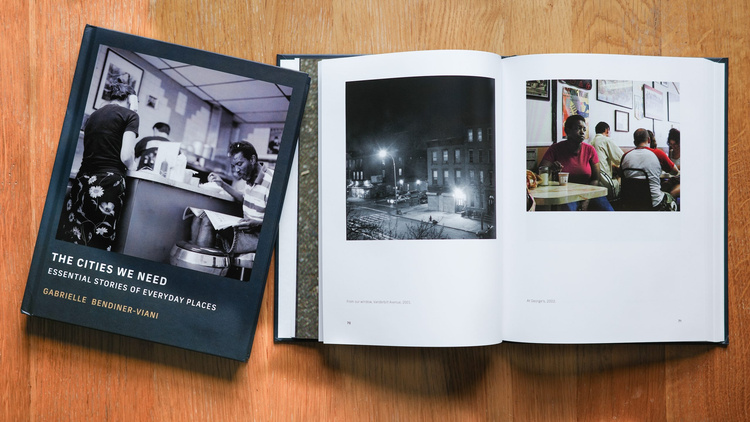

Through a series of photographs, guided walks and conversations spanning the last two decades, photographer and urbanist Gabrielle Bendiner-Viani shows that community is both essential and at risk. The Cities We Need: Essential Stories of Everyday Places makes the complex entanglement of commonplace social bonds that define the places where we live more visible and more tangible (230). She describes the book as being ‘about the work places do to support our becoming’ (36). Accordingly, following the introduction are two sections: Becoming Yourself (61–64) and Becoming Community (165–234), both are composed of four subsections, each of which ends with a modest set of photographs variably labelled ‘portfolios’. The photographs were taken between 2000 and 2015 and work on the book began in 2020 (31). This slow, contemplative kind of work requires an enduring resilience and it can be felt in the well-informed and sincere voice of Bendiner-Viani’s writing. It is a convincing blend of registers that are academic (contextualising the study in existing research), journalistic (pavement-treading investigations), and memoir-like (place-based reflections on friendships, marriage, and childhood).

With specific focus on the cities of Brooklyn, New York, and Oakland, California, The Cities We Need gathers stories about everyday spaces that are in danger, like ‘laundromats, schools, parks, playgrounds, libraries’ (2). Ultimately, this is what the book is about: bringing compassionate attention to overlooked and underimagined places in an attempt to save what might be lost or else to remember what has already been lost. Generally, the research process seems to have three phases. First, Bendiner-Viani walks in neighbourhoods with residents turned tour guides, they offer a unique ‘presentation of self’ (5) whereby they show off their lived experiences and idiosyncratic expertise; then independently she takes digital photographs that range in styles from vernacular snapshots to carefully framed street scenes—this is the expression of her particular photographer’s-eye-view; lastly the photographs are shared with the residents provoking further stories and blooming aural histories. Highlighting the modesty of the study, Bendiner-Viani says that she could never take on a complete understanding of her guides’ day-to-day experiences because every life is different (7). From a theoretical perspective, this is the fitting ‘situatedness’ of her research. In line with that, Bendiner-Viani’s aim is to bring the different perspectives and the different ways people move through the neighbourhoods together so that they are in some ways harmonising with each other (7). The result of those efforts is The Cities We Need. To that extent, the book ultimately reads as documentation of a rigorously academic artistic research practice, at times it even reads like an extended exhibition catalogue. This often leaves the reader feeling like an inactive observer which is an unusual position considering the contemporary urgency for action that some of the topics addressed in the work call for, most notably: gentrification.

From a social science perspective, Bendiner-Viani argues that these ‘small public and semi-private spaces’—think of ‘sidewalks, diners, bus stops, churches, meeting places, barber shops’ (2)—are doing important work in the community, she calls it ‘placework’. It is a common, underappreciated, and necessary kind of work that is ‘laying the ground for a functional society’ (2). It is not a kind of work that produces financial capital, she argues, but instead a kind of ‘social capital’ which can be a means to ‘construct new, and even radical, futures through everyday interactions experienced at a visceral individual level’ (40). What is at stake when placework is compromised is not the loss of an unrealistic folksy cosiness, but is the possibility for dialogue and collective action against social injustices which are exacerbated by the atomising effects of how cities are now being reimagined, remodelled and rebuilt (again: gentrification). Without hyperbole, Bendiner-Viani argues in the conclusion that ‘[i]f we want to be human, we need placework’ (233). For instance, when writing about everyday encounters between neighbours, Bendiner-Viani notes that in those moments it is rare that anything important is said but nonetheless those interactions ‘validate the fact that we’re human, that time passes, that we all feel things, that we feel pain, that we feel happiness, that we’re experiencing the world together’ (40).

Curiously, this could also be used as a description of her photographs; their subject matter may not be profound—a hotdog stand at magic hour (57), a playground under renovation (73), a gas station in twilight (99), and so on—but Bendiner-Viani argues that these places are in urgent need of our attention. As such, the photographs do not need to have a ‘point’ or specific detail to be considered worthwhile or artful, instead it is the broader social and cultural significance of the subjects and environments photographed that matters most. Therefore, when the photographs are coupled with the transcripts from the guided tours, Bendiner-Viani is able to make these places that have very particular localities and unique histories part of a greater global concern. For instance, a 2006 photograph shows an industrial-looking steel staircase leading up to the front door of a house, just like the window next to it the door is behind bars. It is daytime but the bare bulb of a porch light glows orange against the off-white and pale green slats of the exterior wall. There is nobody around but the gate is open, there is a daily newspaper jammed in the fence and a single letter stuck between the bars and frame of the front door, as such the space is not abandoned (at a perfunctory level) but it looks socially disengaged. The caption Bendiner-Viani supplements the photograph with reads: ‘All kinds of people used to be over there’ (33). In the background, out of focus beyond a chain link fence there are other buildings that look like they would offer similar scenes. In this way, with commendable skill, Bendiner-Viani brings an uncommon scale of compassion to these small, mundane places without making them spectacles of interest. This, to some degree, is what differentiates her photographs from other photographers that share similar American(a) subject matter. William Eggleston, as a well-known instance, manages to compose these sorts of banal spaces into an eerie hyper-reality of extreme chromatic complements. In a way, his photographs look to bring order to the aforementioned messiness that Bendiner-Viani is so keen to defend, foster, and remain rooted in.

Whilst her photographs offer a visual articulation of a complex, existential social problem there is little guidance for readers to ‘immerse’ themselves in the images despite her asking them to (3). The accompanying prose explains in longform what the reader is looking at and why it is important to look at from social, cultural, and historical levels but, aesthetically, there is little guidance to help ‘tune’ perceptions to see what is often unseen. As such, Bendiner-Viani uses her photographs as a way to ‘still time, hold on to moments, clarify, critique’ (17) but not necessarily to advance the visual literacy of the people that live in those cities and beyond. That being said, The Cities We Need successfully provokes compassion and empathy in its readers by showing the everyday ‘crisis of place and of dialogue’ (231) in a matter of fact kind of way. Undoubtedly, this will inspire other artists and researchers to do the same in their local neighbourhoods and encourage them to also, as Bendiner-Vianin did, learn about ‘resilience, responsibility, parenting, politics, and the human heart’ (11).