Book Review: Unearthing the Music: Footnotes to Sonic Resistance in Non-democratic Europe (1950-2000)

Reading about music can be like reading about food or sex. When the author isn’t naming parts—ingredients, glands, or in this case: band members and records—they are offering up an unavoidably confessional show of their private tastes and obsessions. Thankfully Unearthing the Music avoids this dullness by focusing on the social, cultural, and political aspects of “sonic resistance” in non-democratic Europe. What the editors call “non-democratic Europe” generally encompasses the East and Southwest, which avoids the more familiar but clunky dichotomy of Europe’s democratic West and non-democratic East. Writing from the far West of Europe, as a Portuguese citizen, Rui Pedro Dâmaso argues that an ideological East-West division overlooks common experiences. What is shared is a feeling of “not quite belonging, of lagging behind, of having missed out on decisive moments that shaped Western culture, of being peripheral, of strenuous hardship for the better part of their recent history.”

In his cautious introduction, Dâmaso shows a well-reasoned degree of self-consciousness (or else: critical thinking) about the risks of writing histories both in their inevitable incompleteness and the dangers of inadvertently fostering “functional amnesia” rather than enhancing public memory. He argues that the aim of the book is not to offer an all-encompassing understanding of music in non-democratic Europe, for not only was the music vastly different but so were the countries it was being made in: Yugoslavia, Ukraine, Portugal, for instance, were non-democratic in their own unique ways. Music journalist Wolf Kampmann makes this diversity clear in his chapter on Jazz, when he compares its differing reputation and reception between Poland, Eastern Germany, and Czechoslovakia. Despite the 600-page heft of this book, it is modestly subtitled as being a collection of “footnotes”. Similarly, describing what the book is doing as “unearthing” supports that same sensible measure: it nods to the inexhaustible labour needed to surpass sediments of things misremembered, romanticised, fetishised and over simplified. It also avoids the more common verb of “discovering” when it comes to talking about ostensibly unknown music. After all, it is a term with problematic connotations of possession and ownership.

Throughout the book there is little formal interest about what the music is—there is rarely mention of instruments or lyrics—instead attention is given to what music as cultural phenomena does and how it comes about. This means that whilst there are lists of bands, gigs, and venues that likely most readers will never have heard of, it rarely reads like the authors are flexing an obscure knowledge for the sake of showing themselves to be “in the know”. Instead, each of the nineteen chapters feel more like the various contributors (journalists, authors, musicians, interviewees) are at a base level sincerely enjoying the opportunity to share their experiences of dissent and resistance; Unearthing the Music isn’t offering a universal history, it is presenting histories as a fracture of personal optics into a recent past. The authority of these histories, as such, comes from the conviction of the voices being platformed more than the credentials of the contributors as experts. In the appended list of contributors, for instance, there are more credits to musicians and journalists than there are researchers. This means that when the chapters are littered with dates and studded with unfamiliar names, the effect is a display of complex entanglements of “actors” in heterogeneous moments rather than the academic cataloguing of an unfamiliar music scene.

The tone set by the unguarded personal accounts of resistance is exemplified, albeit in different ways, in the many interviews. There are traditional music journalism-style interviews, such as Uncompromising: Chris Cutler on Music and Politics in which (and it’s reasonable to assume) the words have been coaxed into their final form; they are less raw and slightly writerlier. That style reads differently to Fifty-five Years of EXS: Memories from the Experimental Studio Bratislava which is a transcript from a Slovak radio program; it has a more drawn-out conversational flow, although the speakers clearly have their remote listeners in mind. In sharp contrast, as part of the chapter New Chicks on the Bloc: Punk in Communism, there is a clipped WhatsApp interview that is an almost offhand but nonetheless insightful exchange between interviewer Pavla Jonssonová and the lead singer of Tožibabe, Mojca Krisch.

There doesn’t seem to be an authoritative red-pen-wielding editor making their mark on the stories told in Unearthing the Music. Rather, what’s offered is a well-fitting idiosyncratic editorial style that allows for a cacophony of differences. In this way, the non-democratic European milieu is not being retrospectively noodled with from the outside but instead being spoken of from the inside out. Even the few texts written by “outsiders”—that is, people from outside this non-democratic context—are written as first-hand testimonies, such as Chris Bohn’s chapter about working for the then UK-owned rock magazine NME when covering the underground music scene of a pre-revolution Prague, Budapest and Warsaw.

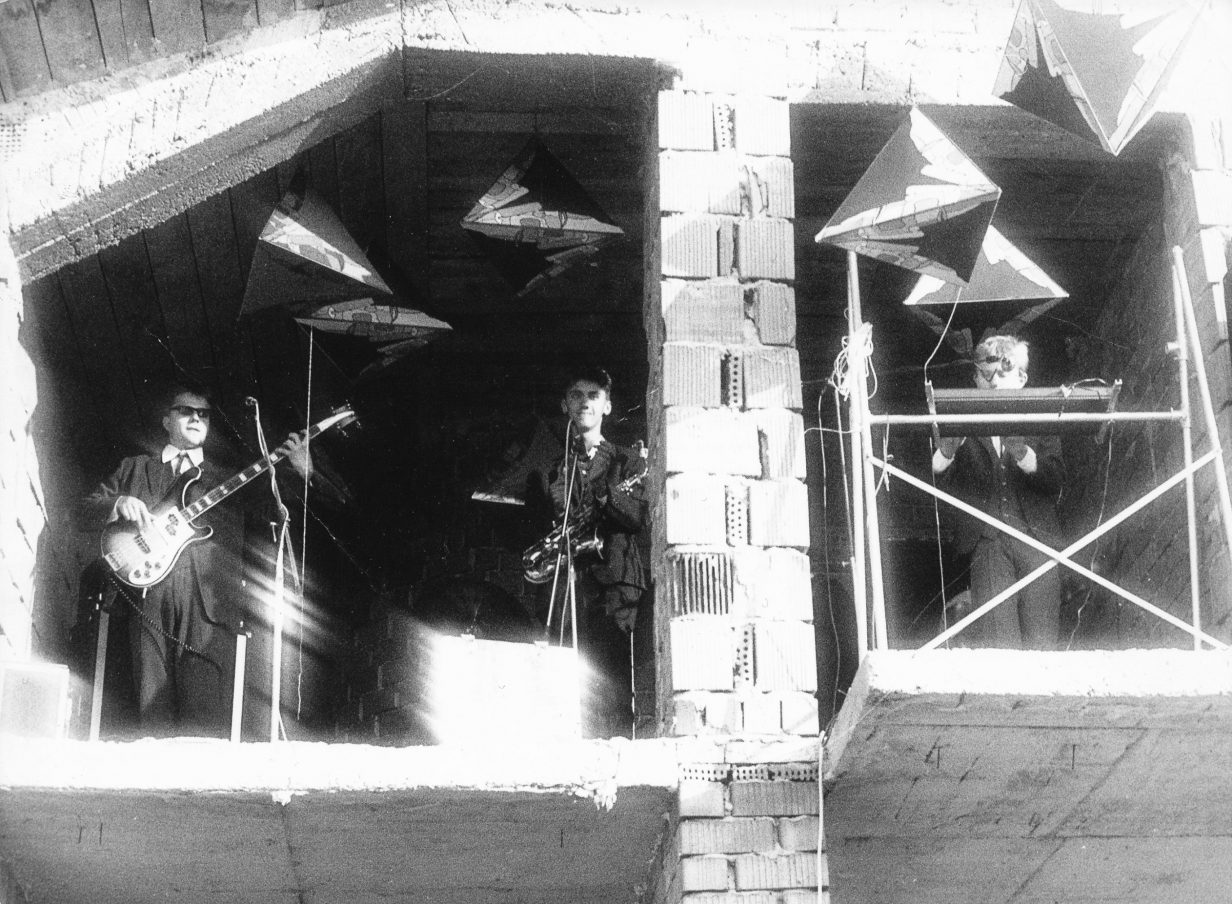

Most of the articles are supplemented by eclectic images that show a mix of ephemera from gig tickets, programs, and posters to snap photographs of tightly packed clandestine performances in unofficial concert rooms. Printed with striking azure blue borders (as opposed to a more “serious” plain white) the images don’t call for constipated, sober reverie. Instead, these histories are being presented as important. They are displayed in ways that are not precious. Some of the larger images are printed as full spreads across two pages which means that part of the image is lost as it falls into the inner margin. This is typically considered a design error but here it is a deliberate effect, bringing attention to the limitation of the book format itself. After all, this medium is just one of many other (differently limited) ways of expressing the same histories. In this and other ways, the book clearly shows itself not to be overly protective of the histories it shares.

It’s probably quite well known now that writing plain-speaking histories and developing public archives of things considered “marginal” both brings that fringe culture to a central attention and also risks that culture being metabolised (and bastardised to boot) into the mainstream culture industry. In other words, making a thing comprehensible and popular risks it becoming a privatised and tradable commodity. Arguably, Unearthing the Music doesn’t need to make too much of an issue with that because any recognition or acknowledgement or representation of these histories makes an inherent problem of the established, overly Western (read: democratic European West) image of what is considered to be punk, experimental, alternative, avant-garde, and so on. Unearthing the Music is implicitly using Europe’s non-democratic past as a way to reflect on, perhaps re-evaluate, its present understanding of what “sonic resistance” is and can be.

There’s an early piece of writing by Friedrich Nietzsche that’s part of his Untimely Meditations, which concerns how history can (and possibly must) serve life. He describes three modes of history: monumental, antiquarian and critical. A “critical” history rejects tradition by taking a knife to its roots. An “antiquarian” history has an “odour of decay” because it obsesses with the past. A “monumental” history, on the other hand, informs and motivates the present by being a reminder of what has come before. Unearthing the Music undoubtedly offers a monumental history of resistance. The challenge of such a history, however, is to avoid the past being embellished as a fiction in the present; it mustn't be parodied according to contemporary aesthetic tastes.

With these ideas in mind, there is little to no guidance in Unearthing the Music on how to read the past in the present, or a suggestion of the broader cultural value of the work itself. Under the surface, it feels like there is something much greater at stake here beyond the knowledge of music in particular socio-political contexts, or the fandom of a scene; it’s unclear exactly what for but there is a subtle urgency to Unearthing the Music.