Book Review: Seeing <—> Making | Room for Thought By Susan Buck-Morss, Kevin McCaughey, Adam Michaels

Seeing <—> Making | Room for Thought is a “collaborative, cross-generational project” between Susan Buck-Morss, Kevin McCaughey, and Adam Michaels. Buck-Morss writes philosophically about images; their questionable ownership, modes of distribution, their everyday affects, and roles in making history and knowledge. McCaughey, a designer with pedagogical interests, plays off Buck-Morss’ writing with unconventional uses of (typo-)graphic images. Michaels, a designer working in publishing—namely Inventory Press, the publisher of this book—assembles their works in an unusual editorial format that reorients the role of the reader from audience-as-whitness to participant-as-collaborator.

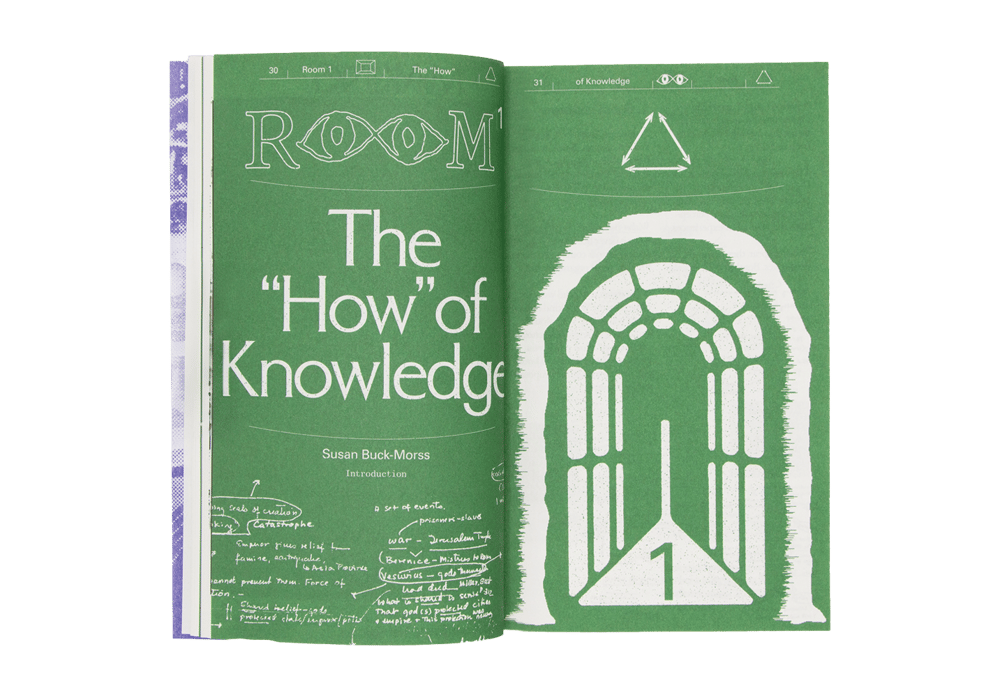

Structurally, Seeing <—> Making | Room for Thought is divided into twelve “rooms”—a metaphor riffed on throughout: make room, reading the room, a space for all to enter, and so on. Each room presents thoughts on images in diverse registers ranging from the reflectively personal (Room 1), to the more philosophically critical (Rooms 3 and 4) and the political (Rooms 7 and 9). The writing is presented as an impishly witty montage of quotes and excerpts that bulge and hang out from the main body of text. Despite a few of the chapters being re-presentations and re-edits of previously published words by Buck-Morss—the oldest from 1992—there is still a contemporary relevance to each of the chapters’ themes.

Alongside the writing is a cacophonous mix of images which are at once illustrative, diagrammatic, tangential, provocative, archival, iconographic, agonistic. They offer a graphic way of thinking critically about images, something that is usually reserved for the (implicitly more serious) textually theoretical. Rooms 10 and 12, for instance, are almost exclusively made up of images, as is Room 6 which is a set of low-resolution, bitmapped graphics that converge juxtaposed scenes such as a carwash from 2010 and a soviet agit-train interior from the 1920s. It's a complex blur that constructively agitates the reader’s attention by dismissing the conventional relationship between text (as primary) and image (as secondary). The pages of Seeing <—> Making | Room for Thought are designed in such a dense way that they urge the reader to flit, back and forth, rather than to move in a uniform march turning from one page to the next. As such, this is a book to return to, over and again as a “self-motivated creative and political activity” (p. 79).

The book often reads as if the centre has been cut from the page leaving only a marginalia of loose ends, elliptical quotes, and stunted excerpts. The effect is that there doesn’t feel to be any lines to read between. Instead, there are scatters of images to pass through and blocks of text to think alongside with. As such, it may have an overall surface appearance of something roughly cobbled together in an anti-design or “new ugly” kind of way but Seeing <—> Making | Room for Thought is undoubtedly a serious experiment in philosophy-as-image and image-as-philosophy. It reads like a book of germs; seeding, sprouting, budding. And, impressively, it manages to stir up and sustain the dynamic quality of philosophical ideas which have so often been deadened by rote exegesis. As such, Seeing <—> Making | Room for Thought will have a broad appeal. For readers looking to gain entry into the philosophy of images this is a noteworthy introduction and a resource to return to. For readers wanting to regain a dreamy enthusiasm for constellations of thought that have become overly familiar, this is a worthwhile sojourn.