Book Review:

Floating Signifiers: Case studies on image, origin and representation

Floating Signifiers: Case studies on image, origin and representation

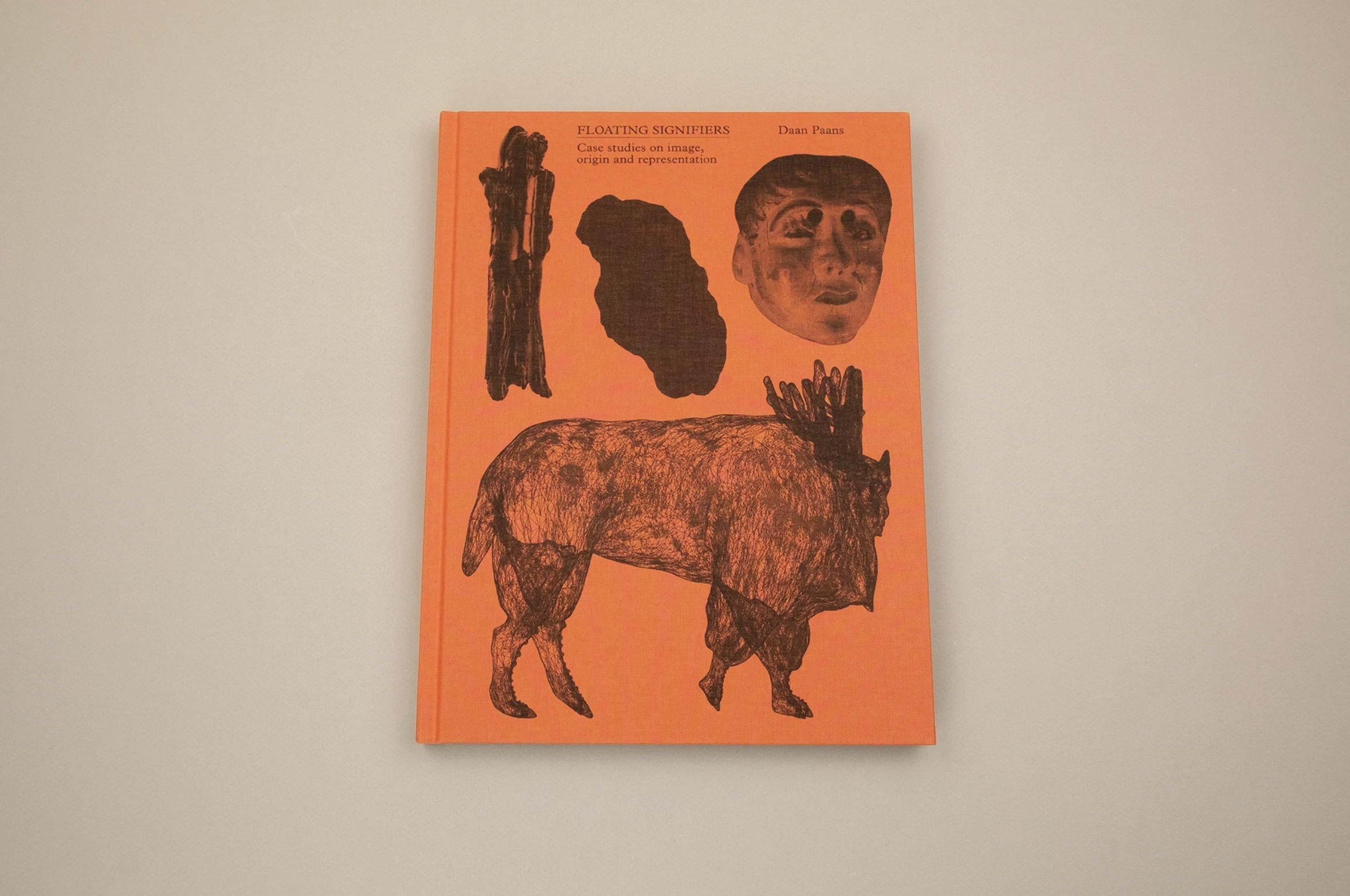

Floating Signifiers: Case studies on image, origin and representation is Daan Paans’ second book with the independent publisher and book designers The Eriskay Connection, whose publications mostly focus on “contemporary storytelling at the intersection of photography, research and writing”. Often, it seems, those stories are told quietly and seen through acute, deeply personal optics, it gives them a fleshy vulnerability and meaningful sincerity. Paans’ latest work is no different. Generally, Floating Signifiers is concerned with the “constant transformation that things and phenomena undergo under the influence of a complex set of factors”. This wonderfully uncooperative description works well to give an awkward density to the book that resists immediate or simple understandings. As such, it fittingly presents itself as existing in the same confusing condition as the subjects written about inside.

Floating Signifiers is a catalogue of nine miscellaneous “case studies” and a closing essay by a guest author. The subjects of the case studies range from rhinoceroses and conquistadores’ masks to oak trees and ancient idols. Each opens with a brief few hundred words that contextualise Paans’ approach to the subject. But this context is not used as a way to explain the value, urgency or worthwhileness of the subject itself, rather it works in an elliptical way to bind the subject to the influences of those previously mentioned “complex set of factors”. Amongst others, these include the influence of Darwin’s theory of evolution, the industrial revolution, the degradation of the natural world, cosmic events, colonialism. In other words, each short introduction is about how the “process of production and reception” of visual materials are wholly dependent on the conditions of possibilities as defined by the cultures from within which they are perceived. Therefore, Paans’ unassuming view is offered as just one among many.

This attitude stems from the freeplay nature of the concept of the “floating signifier”. In fact, the motivations of each case study can be framed in terms of this concept. Unhelpfully for the casual reader, though, the “floating signifier” is not defined in any substantial way in the case study texts nor in the closing essay. It’s possible that what Paans might mean by it is when a representation does not re-present a definite thing but rather another representation, which is itself a re-presentation of other representations, and so on in an unending flow (panta rhei). In this way, a “floating signifier” is something that is not tethered to a simple referent, rather, its referent is an illusive marrow, a contingent essence. With this in mind, a signifier could be described as “floating” when it is indeterminate or else dependent on a particular set of circumstances – cultural theorist Stuart Hall famously described race as a floating signifier, for example. In maintaining these vague qualities of the titular concept, Paans’ book is not really “getting at” anything, so to speak, instead he is presenting undetermined objects in an indeterminate way; the case studies are brief, idiosyncratic, fleeting (and floating). Whether this is intentional is beside the point, what’s clear is that we live in a culture that can not escape its complex historicity and this is cause enough for Paans’ artworks.

Following the text is image, the leading authority of this book. Each case study has a scatter of historical visual research; cobbled across the pages are images of tapestries, film stills, clippings from comics, screenshots, 3d models, scans and photographs that make up the raw material of visual cultures past and present. Closing each case study are original multimedia art works from Paans. In contrast to the research images, the artworks are printed full bleed and feel more like a sequential set of images hung in a gallery to be lingered over, or at least passed by slowly. As such, although it is not said explicitly – and it is not clear why – the book is ultimately a portfolio of Paans’ eclectic work spanning the last ten years.

This is further confirmed in the introductory case study texts which, at times, read like exhibition labels: “Paans attempts to think across time […] Paans creates a layered and dynamic interplay between present and past […] The question that Paans seems to want to address is […]” and so on. Without credit to another author, it’s fair to assume that Paans wrote these texts himself, so it is unclear why the divorced tone of writing in third person was chosen, particularly when these case studies seem so personal. Alternatively, to have this unusual inventory written in first person might have it read as if it were jottings in an artist’s sketchbook, an ethnographer’s field journal, or a historian’s diary. This would heighten the more eccentric quirks that are implicitly layered in each case study and artwork.

The subjects of the case studies are not hazarded to be “read” as cultural scripts but instead are intuited – from Paans’ nondelegable perspective – as relations. As such, Paans looks to be working as a “narrative historian”, as art historian George Kubler might have it, in which he has the “privilege of deciding” that the continuity of these things, this cultural stuff he is interested in, “cuts better into certain lengths than into others”. A good story, Kubler tells us, “can begin anywhere the teller chooses”. In this way, although at a different scale, there is something similar here to Erik Kessels’ recent Incomplete Encyclopedia of Touch, which gathers almost two thousand photographs documenting “the human desire to put a hand on things”. As well as Ilan Manouach’s Harvested, from 2015, which uses crowdsourced services to crop out five-hundred found artworks in the background sets of adult films. On the surface, these narrative histories, like Paans’, are arbitrary and have no definite purpose, but unlike these works Paans risks giving “application” to his scrapbook archives by using them as a chain of signifiers and “datasets” to inform his artworks.

For example, Case Study III is a modest tromp through a history of representations of oak trees. The non-chronological collection of thirty or so images runs from the late 1400s to the recent present. In a similar way to Soyun Park’s The Unflattering Dataset of Machine Learning, Paans uses these oak tree images as a dataset for his artwork Oak Tree 2472 which is a 3D model of an imagined oak tree representation of the future. The artwork is presented in Floating Signifiers as four, crisp full bleed images.

If seen as a portfolio of Paans work, Floating Signifiers can be framed as more of an unsystematic study of an artist’s extraordinary interests. This means, in turn, that the case studies can be understood not as trying to make sense of the world in any reliable or reproducible way but instead as self-consciously making sense from the world. As such, Floating Signifiers reads as an undisciplined and personal history of a visible past articulated through unique, and often compelling, artworks. Despite this, the book is worth your time: it is thought provoking in the way that it addresses familiar themes in contemporary culture in uncommon ways.

Being independent from tweedy academic traditions gives Floating Signifiers a different rhythm that could certainly swerve the reader’s attention in unexpected directions. As such, whilst Nicky Heijmen’s closing essay kicks up relevant names – Baudrillard, Latour, Haraway – which help to map Paans’ work onto better-known academic territories, the opportunity to follow through with Paans’ momentum and set the reader off thinking in different ways fueled by the voices of lesser-known artists and theorists could have been a risk worth taking. Then again, maybe the new narrative historians Floating Signifiers will inspire won’t need such guides and prompts, they might only need to imagine the artful culture of what Kubler called the “useless, beautiful, and poetic things of the world” – and Paans certainly takes us there.

Image courtesy of The Eriskay Connection.