DAMN° 87 – Examining the Dust on his Desk

Considering the everyday ubiquity of design – UX, graphic, product, and so on – it’s surprising that everyday realism is not a more common topic in design’s conversations. Dirty Furniture, the design magazine, certainly offers a thought-provoking alternative to the familiar chrome-polished sheen of high-end furniture publications, and graphic design has never felt as real as it does in Kevin Lo’s latest work Design Against Design, but these are fringe exceptions.

The reason might be that realism treads close to trivialising design, it risks making design (and designers) banal. Adding to that, design tends to be concerned with the general and the universal, whilst realism, on the other hand – if we inherit its more literary definition – emphasises the particular, and the individual; it’s the tear in the bigger picture, so to speak. Perhaps, this kind of realism is too chaotic, too unwieldy for most designers. There is an under-the-nails muckiness to all of this, and designers seem to relish a cleaner, well-kept sort of order.

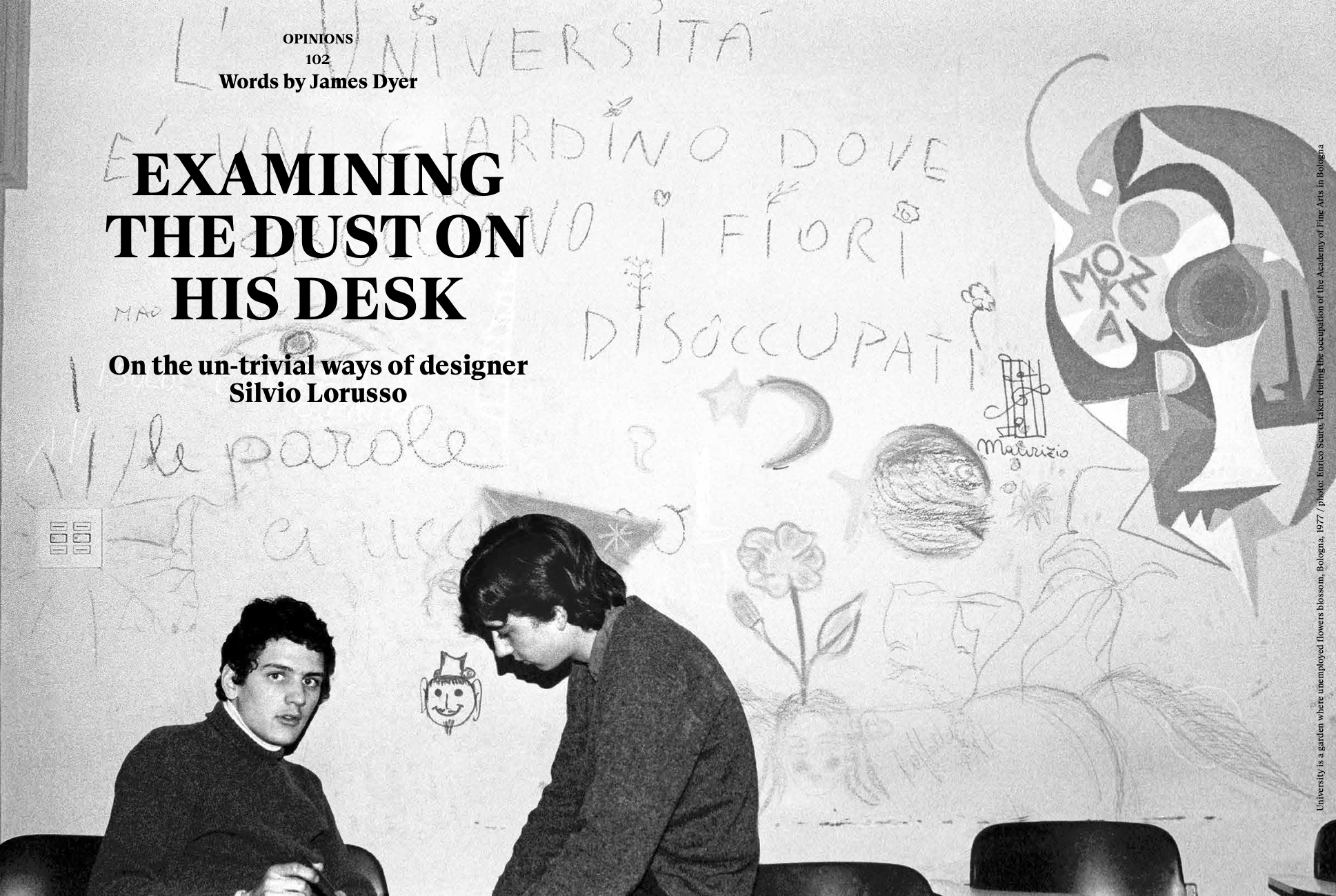

For writer, artist and designer Silvio Lorusso, despite design’s efforts to impose order on the disorderly, the chaos of reality is ever-present whether it is explicitly acknowledged or not. The discordant relationship between chaos and order that Lorusso cogently presents in his latest book, What Design Can’t Do: Essays on Design and Disillusion, feels viscerally similar to the opening scenes of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet: A man collapses in a picturesque garden, the camera descends, past his body, into the grass and down, further to a primordial, lower-level chaos that exists in spite of the kempt lawn above. “Order is always under siege,” says Lorusso, “chaos seeps in, corrupts the magic circle, erodes its contour.” He writes this in the prologue of What Design Can’t Do, which he describes as a “voluminous, block-like book written from a melancholic distance.” Lorusso is not a doomsayer, though, he actually comes across as quite a hopeful pessimist. It’s fitting that I am speaking with him on this day, it’s Carnival where he lives, in Lisbon. As people celebrate subversion, we talk more on the importance of realism in design.

“There is an intrinsic optimism to design, which means it isn’t concerned with the actual state of things, instead it focuses on how things ought to be. And, of course, they ought to be better.” Lorusso goes on to relay a series of turgid articles and blog posts that feel faintly familiar but are recently written. They declare the end of design or else diagnose design to be in crisis, and in a sordid but predictable power-signalling manoeuvre, they claim these issues are the designer’s fault and, ultimately, the designer’s responsibility. “Designers usually speak about their power indirectly, they often package it in terms of responsibility, like the designer's responsibility to do good, or to improve things, or to be responsible for what has gone wrong, like pollution, faulty products or unethical advertising, Gijs de Boer calls it hero baiting.”

Lorusso expresses this discontinuity in design through a well-circulated meme – he has no problem trafficking between Marx and memes or from Philosophy’s footnotes to forum threads – “memes are a lively form of art, and they require a certain kind of cultural literacy,” he tells me, “I take memes seriously and taking them seriously means having fun with them.” They are littered throughout his book, some more tongue-in-cheek than others. In this particular one, there are two lo-fi images stacked. The top one is an obnoxiously hyper-futuristic digital rendering of a sickeningly slick city. The one beneath, a photo of a kitchen sink hoarding dirty, budget crockery. The caption overlaying the top image reads: “Her utopian politics.” The bottom one: “Her kitchen sink.”

In the context of design, the message is clear: a designer’s consuming aspiration for problem solving elevates them to a vantage that overlooks their own disorderly situation. However, playfully, this interpretation can be taken further. Of course, the meme is presenting the contrast between an idealistic utopia (or: “nowhere” as Thomas Moore would have it) and the ever-present mundanity of a domestic sink. The problem is not, however, whether a designer’s fantasy of utopia can, or should, be fulfilled. Rather, the problem is that these virtuous desires of design have been naturalised, they are now part of the soul of design – Lorusso calls it a bourgeois, and sometimes a Victorian soul – which means that it is increasingly difficult to understand what it means to have manufactured these fantasies in the first place. As such, in this instance, we could say that the optimistic desire for utopia acts as a negation of a more pessimistic everyday reality; it is everything but the kitchen sink.

Continuing to over-read this meme, the kitchen sink is the quintessence of what is real. Kitchen sink realism, for instance, became popular in Britain in the late 1950s. The plays, novels, films and TV shows centre around the ordinary-but-not-trivial lives of characters previously overlooked in popular media, think: Harold Pinter, Ken Loach, Mike Leigh, Shelagh Delaney. In kitchen sink realism, a frustrated working class with regional accents in real-to-life scenarios become the counter-conventional vernacular. All this was in direct conflict with the given standard which, at the time, prized not-so-different variations of escapism. This is not too dissimilar to design now. Design has become escapism, it is a way of being absent from real, lived life. And this is all happening at different registers of scale in design too. In a calm, telegrammatic tone, Lorusso describes this “ambiguously polarised” sort of vertigo: “design feels either all-encompassing, infrastructural, planetary, big, baffling – or improvisational, ad-hoc, tiny, volatile.”

I ask him if realism is too radical for contemporary design, “it really doesn't matter if it is radical or not, it is just necessary, a more realist understanding of what a designer can do in the world needs to be developed. Anyway, radical is a term that has been over-consumed, what is really radical now is probably not even identifying itself as radical. People have always called for a return to the real, there is nothing new to that, but what they have believed to be real has not always been the same.”

For Lorusso, realism is a way to "tame professional narcissism," it’s a kind of compromise that, he says, makes a designer vulnerable and fragile. He writes: “compromise is the antithesis of critical autonomy. It is an admission of the fact that the designer is, after all, inevitably a bricoleur – a person who makes do with what they find, in the conditions in which they find themselves.” Through this kind of realism, which acknowledges inherent limitations, albeit from a pessimist’s-eye-view, designers may be able to “notice the dilemma of contemporary professionalism and the fallibility of their tools.”

Lorusso, it seems, wants to bring designers back to something of a modest, domestic interiority. But rather than using this as an excuse to think about the “murky self, which often ends in some kind of morbid lamentation” he wants designers to get back to something true to themselves without being selfish, without harbouring inflated self-importance. “I began writing this book somewhere between being a post-graduate and becoming an assistant professor, it was the moment when I began to feel unconvinced by the professional rhetoric of design. The original essays were juvenile and ranty, but sincere. The tone of this book is much calmer, but the heart-felt frustration is still in the undercurrent. Ultimately, in content and design, I want What Design Can’t Do to have the feeling of a testament. As such, I will say one last thing about the kind of realism I propose; it is concrete and tangible and yet it is the effervescent atmosphere of hope and imagination. It is the dust on the screen that you look past while prepping a slide deck or joining vector points. It can not happen out there, in that nowhere-place, where the absurdly boundless optimism of contemporary design flounders. It has to happen here, where you are right now.

The reason might be that realism treads close to trivialising design, it risks making design (and designers) banal. Adding to that, design tends to be concerned with the general and the universal, whilst realism, on the other hand – if we inherit its more literary definition – emphasises the particular, and the individual; it’s the tear in the bigger picture, so to speak. Perhaps, this kind of realism is too chaotic, too unwieldy for most designers. There is an under-the-nails muckiness to all of this, and designers seem to relish a cleaner, well-kept sort of order.

For writer, artist and designer Silvio Lorusso, despite design’s efforts to impose order on the disorderly, the chaos of reality is ever-present whether it is explicitly acknowledged or not. The discordant relationship between chaos and order that Lorusso cogently presents in his latest book, What Design Can’t Do: Essays on Design and Disillusion, feels viscerally similar to the opening scenes of David Lynch’s Blue Velvet: A man collapses in a picturesque garden, the camera descends, past his body, into the grass and down, further to a primordial, lower-level chaos that exists in spite of the kempt lawn above. “Order is always under siege,” says Lorusso, “chaos seeps in, corrupts the magic circle, erodes its contour.” He writes this in the prologue of What Design Can’t Do, which he describes as a “voluminous, block-like book written from a melancholic distance.” Lorusso is not a doomsayer, though, he actually comes across as quite a hopeful pessimist. It’s fitting that I am speaking with him on this day, it’s Carnival where he lives, in Lisbon. As people celebrate subversion, we talk more on the importance of realism in design.

“There is an intrinsic optimism to design, which means it isn’t concerned with the actual state of things, instead it focuses on how things ought to be. And, of course, they ought to be better.” Lorusso goes on to relay a series of turgid articles and blog posts that feel faintly familiar but are recently written. They declare the end of design or else diagnose design to be in crisis, and in a sordid but predictable power-signalling manoeuvre, they claim these issues are the designer’s fault and, ultimately, the designer’s responsibility. “Designers usually speak about their power indirectly, they often package it in terms of responsibility, like the designer's responsibility to do good, or to improve things, or to be responsible for what has gone wrong, like pollution, faulty products or unethical advertising, Gijs de Boer calls it hero baiting.”

Lorusso expresses this discontinuity in design through a well-circulated meme – he has no problem trafficking between Marx and memes or from Philosophy’s footnotes to forum threads – “memes are a lively form of art, and they require a certain kind of cultural literacy,” he tells me, “I take memes seriously and taking them seriously means having fun with them.” They are littered throughout his book, some more tongue-in-cheek than others. In this particular one, there are two lo-fi images stacked. The top one is an obnoxiously hyper-futuristic digital rendering of a sickeningly slick city. The one beneath, a photo of a kitchen sink hoarding dirty, budget crockery. The caption overlaying the top image reads: “Her utopian politics.” The bottom one: “Her kitchen sink.”

In the context of design, the message is clear: a designer’s consuming aspiration for problem solving elevates them to a vantage that overlooks their own disorderly situation. However, playfully, this interpretation can be taken further. Of course, the meme is presenting the contrast between an idealistic utopia (or: “nowhere” as Thomas Moore would have it) and the ever-present mundanity of a domestic sink. The problem is not, however, whether a designer’s fantasy of utopia can, or should, be fulfilled. Rather, the problem is that these virtuous desires of design have been naturalised, they are now part of the soul of design – Lorusso calls it a bourgeois, and sometimes a Victorian soul – which means that it is increasingly difficult to understand what it means to have manufactured these fantasies in the first place. As such, in this instance, we could say that the optimistic desire for utopia acts as a negation of a more pessimistic everyday reality; it is everything but the kitchen sink.

Continuing to over-read this meme, the kitchen sink is the quintessence of what is real. Kitchen sink realism, for instance, became popular in Britain in the late 1950s. The plays, novels, films and TV shows centre around the ordinary-but-not-trivial lives of characters previously overlooked in popular media, think: Harold Pinter, Ken Loach, Mike Leigh, Shelagh Delaney. In kitchen sink realism, a frustrated working class with regional accents in real-to-life scenarios become the counter-conventional vernacular. All this was in direct conflict with the given standard which, at the time, prized not-so-different variations of escapism. This is not too dissimilar to design now. Design has become escapism, it is a way of being absent from real, lived life. And this is all happening at different registers of scale in design too. In a calm, telegrammatic tone, Lorusso describes this “ambiguously polarised” sort of vertigo: “design feels either all-encompassing, infrastructural, planetary, big, baffling – or improvisational, ad-hoc, tiny, volatile.”

I ask him if realism is too radical for contemporary design, “it really doesn't matter if it is radical or not, it is just necessary, a more realist understanding of what a designer can do in the world needs to be developed. Anyway, radical is a term that has been over-consumed, what is really radical now is probably not even identifying itself as radical. People have always called for a return to the real, there is nothing new to that, but what they have believed to be real has not always been the same.”

For Lorusso, realism is a way to "tame professional narcissism," it’s a kind of compromise that, he says, makes a designer vulnerable and fragile. He writes: “compromise is the antithesis of critical autonomy. It is an admission of the fact that the designer is, after all, inevitably a bricoleur – a person who makes do with what they find, in the conditions in which they find themselves.” Through this kind of realism, which acknowledges inherent limitations, albeit from a pessimist’s-eye-view, designers may be able to “notice the dilemma of contemporary professionalism and the fallibility of their tools.”

Lorusso, it seems, wants to bring designers back to something of a modest, domestic interiority. But rather than using this as an excuse to think about the “murky self, which often ends in some kind of morbid lamentation” he wants designers to get back to something true to themselves without being selfish, without harbouring inflated self-importance. “I began writing this book somewhere between being a post-graduate and becoming an assistant professor, it was the moment when I began to feel unconvinced by the professional rhetoric of design. The original essays were juvenile and ranty, but sincere. The tone of this book is much calmer, but the heart-felt frustration is still in the undercurrent. Ultimately, in content and design, I want What Design Can’t Do to have the feeling of a testament. As such, I will say one last thing about the kind of realism I propose; it is concrete and tangible and yet it is the effervescent atmosphere of hope and imagination. It is the dust on the screen that you look past while prepping a slide deck or joining vector points. It can not happen out there, in that nowhere-place, where the absurdly boundless optimism of contemporary design flounders. It has to happen here, where you are right now.