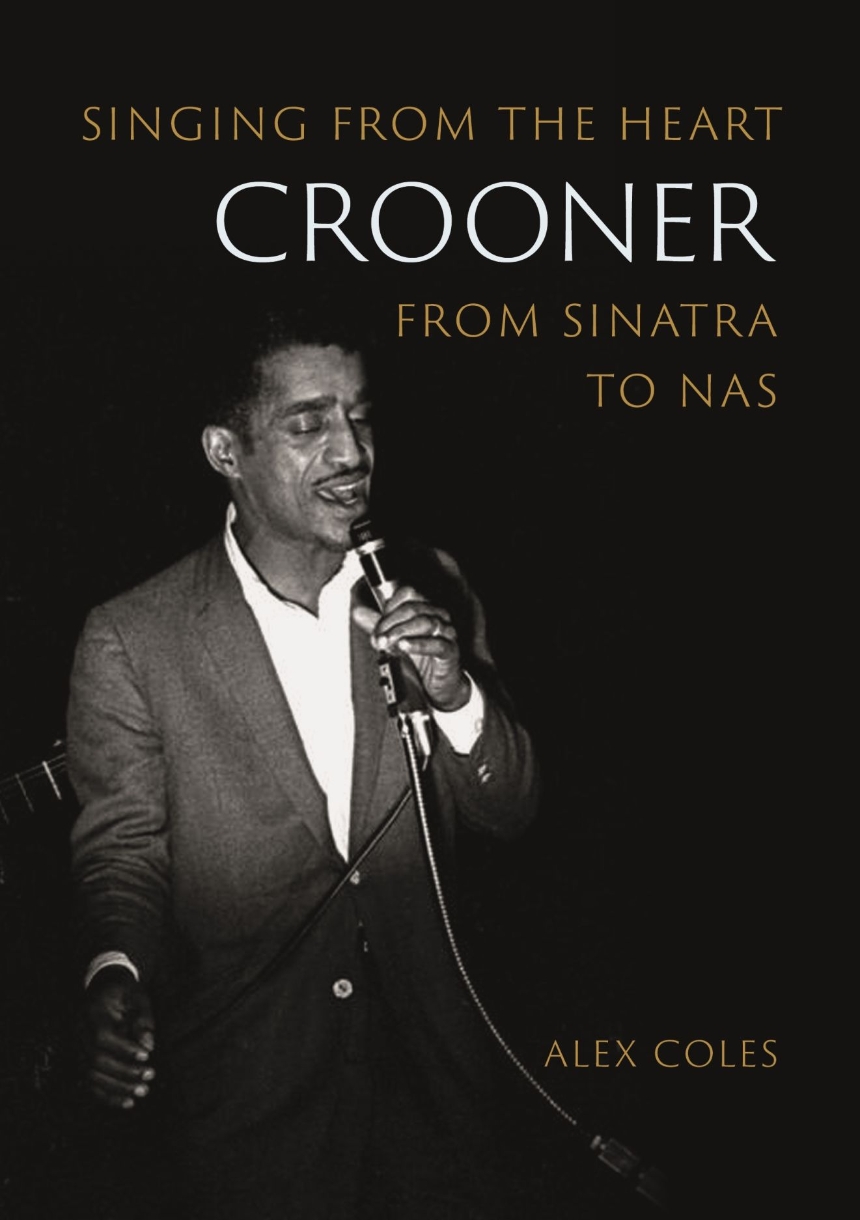

Crooner: Singing from the Heart from Sinatra to Nas (review)

A review for Taylor and Fancis’ Popular Music and Society of Crooner: Singing from the Heart from Sinatra to Nas (2023), written by Alex Coles, published by Reaktion Books as part of their Reverb series.

Crooner: Singing from the Heart from Sinatra to Nas is part of Reaktion Books’ Reverb series. Established in 2010, it is a series that swerves the more predictable biographies and traditional histories of popular music. Instead, books published under Reverb focus on situating popular music in much broader historical and deeper cultural contexts. Alex Coles skillfully achieves this with his imaginative, radical history of the crooner.

It is made explicit from the start, and not repeated until the conclusion, that the aim of Crooner is to reanimate the underappreciated history of crooning. Coles claims that “[n]o other archetype has been as persistent as the crooner in the past sixty years, and no other archetype has been so continually overlooked by music historians” (176). Throughout, Coles characterises the crooner as an icon running vein-like through diverse spreads of popular music genres from disco (55-70) to reggae (111-128) to hip hop (159-172) and more. Careful to define the limits of this ambitious study and manage the reader’s expectations, Coles clarifies that Crooner is not a “musicological study” or a “sociological analysis”, rather “Crooner seeks to simultaneously describe the impact each voice has on the archaeology of the archetype” (8).

On the surface, this aim is plain to see, even in the table of contents there is a definite focus on specific songs from unique voices, some more predictable, such as “Frank Sinatra: ‘What’s New?’ (1958)” (21-36) and others less so, such as “Ian McCulloch: ‘Ocean Rain’ (1984)” (129-142) and “Nas: ‘Bye Baby’ (2012)” (159-172). However, the title of the book and its chapter structure are misleading. Crooner does not depart from Sinatra to arrive at Nas. Rather, Sinatra never leaves the tail of Coles' eye throughout Crooner; each musician, it seems, is a footnote to Sinatra. As such, the unspoken thesis of Crooner could be described as something like the hauntology of Frank Sinatra. This is starkly clear in the conclusion of Crooner where a surreal vision of a reanimated, zombie-style Sinatra mash-up album titled Far from Me is imagined (177).

Popular music is a new territory for Coles. He first wrote Crooner: Singing from the Heart From Sinatra to Nas and shortly followed with Tainted Love: From Nina Simone to Kendrick Lamar (2023) – both works, impressively, were published in the same year. Looking at Coles’ bibliography, he wrote about art before he wrote about design. There are occasional gestures in Crooner that point to this and offer unique, well informed insights beyond the regular scope of a study in popular music. Such as in the chapter “Bryan Ferry: ‘When She Walks (in the Room)’ (1978)” (83-94) in which Coles suggests Ferry treats songs as “readymades” inline with artists Richrad Hamilton and Marcel Duchamp (83), or how Bowie worked with fashion designer Ola Hudson to develop his character the Thin White Duke (74). Now turning his designArt writer’s attention to music, there is an unmistakable eagerness in the voice of Crooner to make this new territory vivid.

Coles begins his history of crooning not with a year, or a singer, an album, a song, a shift or a turn but with a single lyric poured out by Frank ‘The Swooner’ Sinatra during a live tv show performance (10). At first pass this absurd origin reads as hyperbole but as Crooner goes on it is soon clear to see that it is written earnestly. The way this shifty-yet-charming origin sets crooning in motion gives a unique and curious wash of colour to the rest of Coles’ story of the titular "peripatetic shapeshifter" (17).

Whilst there is clearly a linear plan in the development of the crooner, there is also another pinballing layer to the narrative that moves between miscellaneous cultural anecdotes and oblique references such as Sinatra on the phone to Paul McCartney “asking for a song” (12), or the collaborative album between Barry White and Marin Gaye that was never made (70). It is this dexterity of storytelling, which Coles delivers with sincere conviction, that wins the reader over and keeps them locked in to his crooner narrative.

Each chapter moves at a considerable, compulsive, pace. Stylistically, it is not difficult to imagine clipped versions of these chapters as serialised articles in 1970’s issues of Playboy magazine. Not only because they operate independently of each other – which affords a closed circuit repetition of sources, namely: Susan Sontag – but also because Coles writes in a way that is lucid and down to earth. However, despite this accessible groundedness, he does well to avoid a conversational tone that would compromise the academic formality of the writing, for example, he never addresses the reader, nor offers questions to them either. That being said, the register of writing in Crooner is unmistakably talkative. This may be the pleasure of the text but it may also come at the cost of leaving the reader feeling passive.

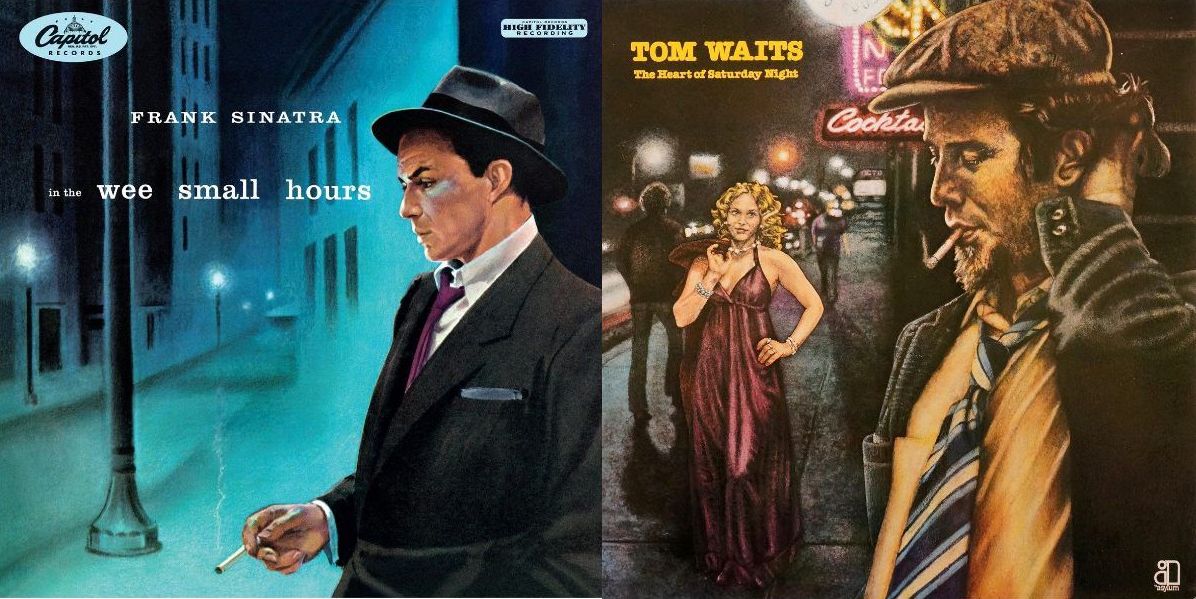

With each chapter saturated with references the frequent illustrations do well to bring a sense of humanity to the crooner’s lived life. Stylistically, they look like glossy photographs a fan would take to a live show hoping for an autograph. Crooner is undoubtedly a book written with passion for crooning, but Coles balances that passion with measured insights and a carefully crafted narrative. More than mindful listening at a cool distance, Coles offers a closeness that is more personal, perhaps quasi-fanatical. With little to no abstract, meta-analysis that would explain crooning away into a confusing fog of theory, Coles’ post-critical writing delivers a rich, vibrant genealogy of crooning. This accessible study will appeal to more casual fans of music – and not exclusively fans of crooning – whilst also holding court in academic circles for those looking to follow Coles’ idiosyncratic tracing of the crooked timber of crooning.

Crooner would undoubtedly benefit from a list of further reading that expands beyond the current list of works cited. This would compliment and advance the few sparse acknowledgements to more critical theory and would bolster the academic currency of this work. It may also serve to make the book more of a springboard for further research on crooning or for more histories to be woven in a similar style for other underappreciated genres and forgotten music icons.

Works Cited

Coles, Alex. Tainted Love: From Nina Simone to Kendrick Lamar. Sternberg Press, 2023.

Crooner: Singing from the Heart from Sinatra to Nas is part of Reaktion Books’ Reverb series. Established in 2010, it is a series that swerves the more predictable biographies and traditional histories of popular music. Instead, books published under Reverb focus on situating popular music in much broader historical and deeper cultural contexts. Alex Coles skillfully achieves this with his imaginative, radical history of the crooner.

It is made explicit from the start, and not repeated until the conclusion, that the aim of Crooner is to reanimate the underappreciated history of crooning. Coles claims that “[n]o other archetype has been as persistent as the crooner in the past sixty years, and no other archetype has been so continually overlooked by music historians” (176). Throughout, Coles characterises the crooner as an icon running vein-like through diverse spreads of popular music genres from disco (55-70) to reggae (111-128) to hip hop (159-172) and more. Careful to define the limits of this ambitious study and manage the reader’s expectations, Coles clarifies that Crooner is not a “musicological study” or a “sociological analysis”, rather “Crooner seeks to simultaneously describe the impact each voice has on the archaeology of the archetype” (8).

On the surface, this aim is plain to see, even in the table of contents there is a definite focus on specific songs from unique voices, some more predictable, such as “Frank Sinatra: ‘What’s New?’ (1958)” (21-36) and others less so, such as “Ian McCulloch: ‘Ocean Rain’ (1984)” (129-142) and “Nas: ‘Bye Baby’ (2012)” (159-172). However, the title of the book and its chapter structure are misleading. Crooner does not depart from Sinatra to arrive at Nas. Rather, Sinatra never leaves the tail of Coles' eye throughout Crooner; each musician, it seems, is a footnote to Sinatra. As such, the unspoken thesis of Crooner could be described as something like the hauntology of Frank Sinatra. This is starkly clear in the conclusion of Crooner where a surreal vision of a reanimated, zombie-style Sinatra mash-up album titled Far from Me is imagined (177).

Popular music is a new territory for Coles. He first wrote Crooner: Singing from the Heart From Sinatra to Nas and shortly followed with Tainted Love: From Nina Simone to Kendrick Lamar (2023) – both works, impressively, were published in the same year. Looking at Coles’ bibliography, he wrote about art before he wrote about design. There are occasional gestures in Crooner that point to this and offer unique, well informed insights beyond the regular scope of a study in popular music. Such as in the chapter “Bryan Ferry: ‘When She Walks (in the Room)’ (1978)” (83-94) in which Coles suggests Ferry treats songs as “readymades” inline with artists Richrad Hamilton and Marcel Duchamp (83), or how Bowie worked with fashion designer Ola Hudson to develop his character the Thin White Duke (74). Now turning his designArt writer’s attention to music, there is an unmistakable eagerness in the voice of Crooner to make this new territory vivid.

Coles begins his history of crooning not with a year, or a singer, an album, a song, a shift or a turn but with a single lyric poured out by Frank ‘The Swooner’ Sinatra during a live tv show performance (10). At first pass this absurd origin reads as hyperbole but as Crooner goes on it is soon clear to see that it is written earnestly. The way this shifty-yet-charming origin sets crooning in motion gives a unique and curious wash of colour to the rest of Coles’ story of the titular "peripatetic shapeshifter" (17).

Whilst there is clearly a linear plan in the development of the crooner, there is also another pinballing layer to the narrative that moves between miscellaneous cultural anecdotes and oblique references such as Sinatra on the phone to Paul McCartney “asking for a song” (12), or the collaborative album between Barry White and Marin Gaye that was never made (70). It is this dexterity of storytelling, which Coles delivers with sincere conviction, that wins the reader over and keeps them locked in to his crooner narrative.

Each chapter moves at a considerable, compulsive, pace. Stylistically, it is not difficult to imagine clipped versions of these chapters as serialised articles in 1970’s issues of Playboy magazine. Not only because they operate independently of each other – which affords a closed circuit repetition of sources, namely: Susan Sontag – but also because Coles writes in a way that is lucid and down to earth. However, despite this accessible groundedness, he does well to avoid a conversational tone that would compromise the academic formality of the writing, for example, he never addresses the reader, nor offers questions to them either. That being said, the register of writing in Crooner is unmistakably talkative. This may be the pleasure of the text but it may also come at the cost of leaving the reader feeling passive.

With each chapter saturated with references the frequent illustrations do well to bring a sense of humanity to the crooner’s lived life. Stylistically, they look like glossy photographs a fan would take to a live show hoping for an autograph. Crooner is undoubtedly a book written with passion for crooning, but Coles balances that passion with measured insights and a carefully crafted narrative. More than mindful listening at a cool distance, Coles offers a closeness that is more personal, perhaps quasi-fanatical. With little to no abstract, meta-analysis that would explain crooning away into a confusing fog of theory, Coles’ post-critical writing delivers a rich, vibrant genealogy of crooning. This accessible study will appeal to more casual fans of music – and not exclusively fans of crooning – whilst also holding court in academic circles for those looking to follow Coles’ idiosyncratic tracing of the crooked timber of crooning.

Crooner would undoubtedly benefit from a list of further reading that expands beyond the current list of works cited. This would compliment and advance the few sparse acknowledgements to more critical theory and would bolster the academic currency of this work. It may also serve to make the book more of a springboard for further research on crooning or for more histories to be woven in a similar style for other underappreciated genres and forgotten music icons.

Works Cited

Coles, Alex. Tainted Love: From Nina Simone to Kendrick Lamar. Sternberg Press, 2023.