Book Review: A Prague Flâneur by Vítězslav Nezval

Despite its lack of fixed direction or definite purpose, A Prague Flâneur (originally Pražský chodec) is rooted in the parks, streets, bars, and cafes of Prague in a surprisingly concrete way. From the street level, as the author Vítězslav Nezval sees it, Prague surpasses its “practical necessity” and expands into a dynamic host for memories, a rouser of imagination, and a stage peopled with extraordinary characters. This “peripatetic book” sketches a Prague that is uniquely personal to Nezval.

According to the translator, Jed Slast, the finished manuscript was likely delivered “September, 1938, if not early October,” only months before the Nazi invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939. As Nezval wrote about his loves, friendships, and youthful memories of Prague, he was also exposing the city’s fragility; so much of what makes up a place is the temperamental relations of its inhabitants, much more than its bricks and mortar. As such, the book exhibits an underlying existential dread of ruin, both of the city itself and also of Nezval’s independent political expression and his friendships with other avant-garde artists. At one point, Nezval writes forlornly: “the droning of the bombers flying overhead has made clear, there is no time, time flies by and tomorrow might be too late.”

There are two versions of A Prague Flâneur. In the more commonly available “expurgated” version, Nezval self-censored the text by removing references to “André Breton, Sigmund Freud, Marx, Lenin, Stalin, Surrealism, the proletariat and so on.” It’s likely that this version was an attempt to make the book “less overtly objectionable to Nazi prejudices.” The edition in review here, published by Twisted Spoon Press, is the first English translation of the original uncensored version. In this edition, the translator has included an appendix of alterations detailing Nezval’s major and minor edits. Littered with square brackets, strikethroughs, and notes from the editor, the appendix is not a straightforward read, but it is worthwhile documentation for readers interested in the finer details of Nezval’s thinking.

The book’s lack of obvious structure and conventional literary signposting—no table of contents, chapters, or subheadings—invites a perambulatory reader, one able to move with Nezval’s words in the same way he moved through Prague’s streets: “only for the pleasure of walking.” Each step is a meaningfully meaningless digression loaded with curious possibilities. Nezval tells us: “When we walk—and especially when we walk with no destination in mind—the faint images of our desire impose themselves on our steps and prevents us from seeing its end, its converse.” Despite the absence of an explicit structure, at times Nezval’s tone shifts in ways that suggest facades of structural difference. This happens four times.

First is what could be considered the introduction, a memoir provoked by everyday places in Prague. In these pages, Nezval is both wistful and excitable as he describes the way his personhood is fused with the city. The surrealistic qualities of chance, surprise, the implausible, and the extraordinary are vivid from the start. Nezval writes: “I was momentarily astonished that my steps were unwittingly taking me to the Kinský Garden,” where he sits on a bench and finds, to his surprise, his name carved in the seat or how he “unexpectedly found [himself] among the streets of Vinohrady.” There is something plain-faced about the surrealism here: it is not a clunky aesthetic device, but a sincere worldview.

In this section, the reader is introduced to Prague via a stream of names of streets, cafes, restaurants, artists, bridges, bars, and neighborhoods. For a reader unfamiliar with the city, the density of names could be grating and may interrupt the flow of their meander. Yet, the back of the book, after the appendix, features notes that aim to orient the reader. These are insightful and undoubtedly valuable if, ironically, a little challenging to navigate. This awkwardness is probably due to the editor’s faithfulness to the original book, or reticence to include superscript numbers or annotations in Nezval’s original text. While this section is not dependable—readers may often look for notes that don’t exist— it is still a useful resource for readers looking to give further context to Nezval’s steps.

Nezval then explains the tensions between the artists of the Paris and Czechoslovakia Surrealist Groups. This is clearly a tender subject for him. In the late 1930s, he was being pushed from “the group [he] had founded” and publicly slighted in their “whisper campaign” because of his continued support for the Soviet Union. This section is written cautiously and stiffly with an unconvincing tone of disinterest. Perhaps a little coldly, the translator describes this part of the book as going into “tedious detail” about the altercation. More charitably, this section reads as if Nezval was writing in the hope that the artists he once called friends might read his words and be more compassionate to his differences. Despite the cautious language, his upset is heartfelt. He writes with disappointment about the bonds lost with “those whom for years [he] had never stopped placing in the light of [his] dream.”

The third tonal shift is a philosophical explication of what constitutes “reality” and “dream” and other related matters of Surrealism, such as “écriture automatique” (or: automatic writing). This section reads like it could be published independent of A Prague Flâneur entirely; it wouldn’t be surprising to find it reprinted in a magazine or in a book of collected artists’ essays. The book’s ending is a playfully surreal, farcical, anti-conclusion, which Nezval doesn’t seem entirely convinced by. The final pages display a deliriousness in which Nezval’s memories and imagination—along with the coarse materialities of Prague—are stirred together to a miasmic effect.

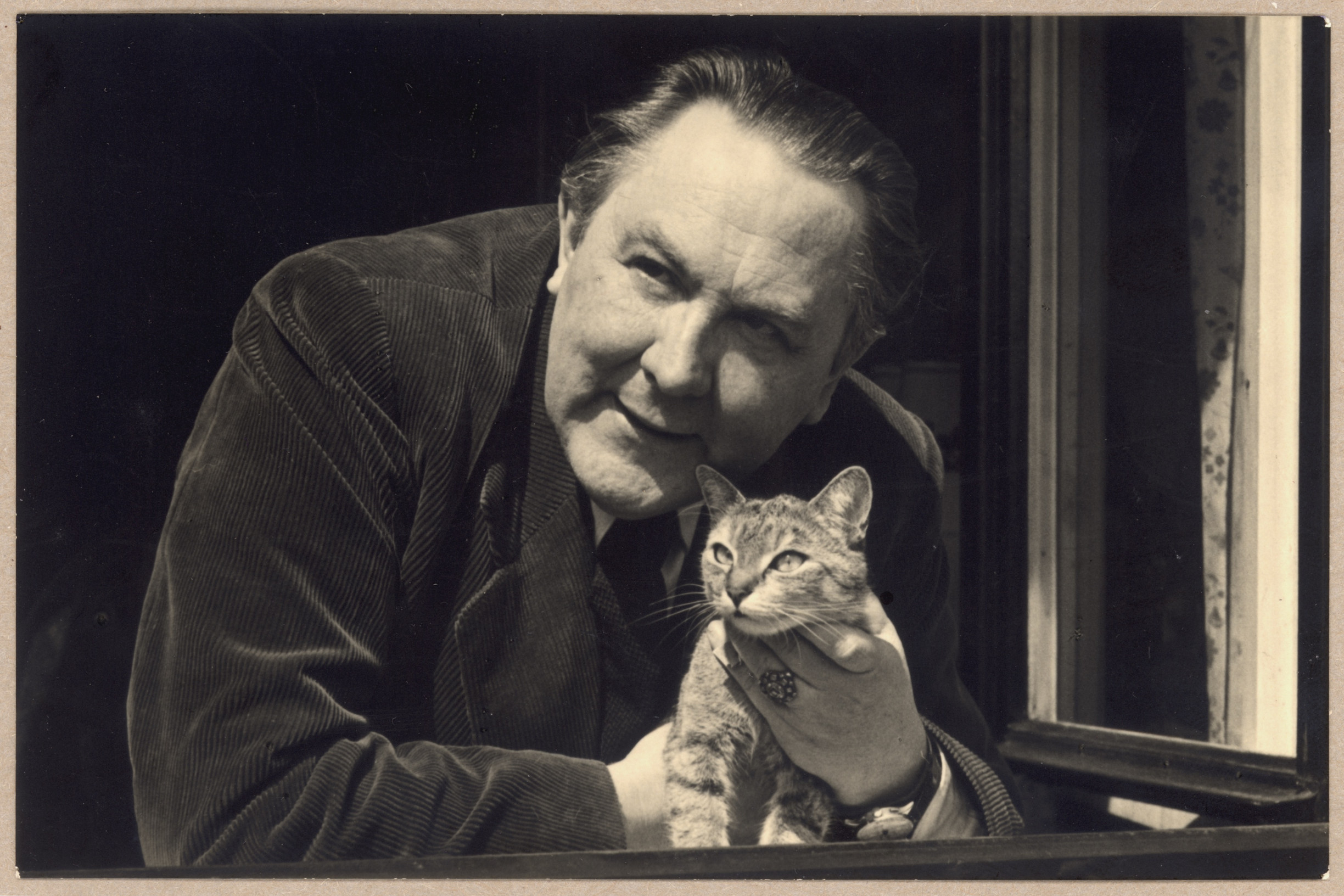

A Prague Flâneur is sparsely illustrated, mostly with black and white photographs taken by Nezval. They look like impromptu snaps, shot from the hip, without too much consideration of framing or exposure. In other words, they are not picturesque. Even the subjects of the photographs seem inane, near arbitrary: an open doorway with an illegible sign, an almost empty cobbled street with flags blowing in the wind, a canal seen from under a bridge. These photographs work well to bring the reader back to the banal material of the places Nezval writes about; the real to his surreal. Furthering that bond to the real is the effect of the poor reproduction of the photographs. Their grainy distortions are a chance reminder of the constructive fallibility of perception and the unavoidable aberrations in the creative interpretations of those perceptions. Whilst crisp prints on more appropriate paper stock would have represented his pictures more faithfully (and increased the cost of the book) there is something more valuable in these low fidelity reproductions.

A Prague Flâneur reads as an individual’s lonely account of being with people in a city that inspires dreams to no end. Nezval admits that the things he is drawn to may not be unique to Prague, but that he cares about the fact that these “certain spontaneously intoxicating situations” occurred there. A Prague Flâneur is more than a historical account of an artist’s vision: it is also a provocation for readers to think of their own sentimental attachments to the places where they live and the lives that they share. When Nezval describes his method as “the interpretation of reality in a way that singularly embodies revelation through imagination,” readers may remember that, even in the face of adversarial times, dreaming is still a radical possibility.